Arc Institute's Virtual Cell Challenge: Are We Modelling Cells or Just Their Fingerprints?

What participants learned about data limits, metrics, and why big models didn’t tell the full story.

Welcome back to your weekly dose of AI news for life science.

What’s your biggest time sink in the drug discovery process?

Most people expected the Virtual Cell Challenge to be a showcase for big models and bigger compute.

What it became instead was a reality check. Not just about AI, but about data, biology, and what we actually mean when we say “virtual cells.”

To understand why, I spoke with Giovanni Marco Dall’Olio, a computational biologist who took part in the challenge and followed the post-competition discussions closely. His experience training models, watching them fail, and debating metrics with other participants mirrors what many teams quietly went through.

Here’s what the first real stress test for virtual cells revealed.

The first real stress test for virtual cells

When the Arc Institute launched the Virtual Cell Challenge, it felt like a moment the field had been circling for years. A public competition. Real data. Serious sponsors. A NeurIPS-stage finale. For anyone working at the intersection of AI and biology, this was not just another leaderboard. It was a chance to see what actually holds up when theory meets friction.

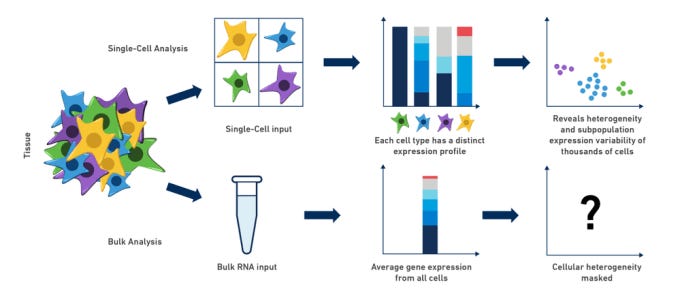

The goal was simple to state and brutally hard to execute. Predict how cells respond to genetic perturbations. Not in a toy setup. Not with hand-picked examples. But across dozens of perturbations, thousands of genes, and single-cell data that behaves more like weather than physics.

Expectations ran high. Foundation models would dominate. Compute would carry the day. Then, as Gio put it, many teams ran into the same wall. Models that would not converge. Training runs that went nowhere and an uneasy feeling that the bottleneck was not GPUs.

The “simple models might win” panic

Early in the challenge, a quiet anxiety spread through the community. What if all this effort collapsed into linear regression beating transformers?

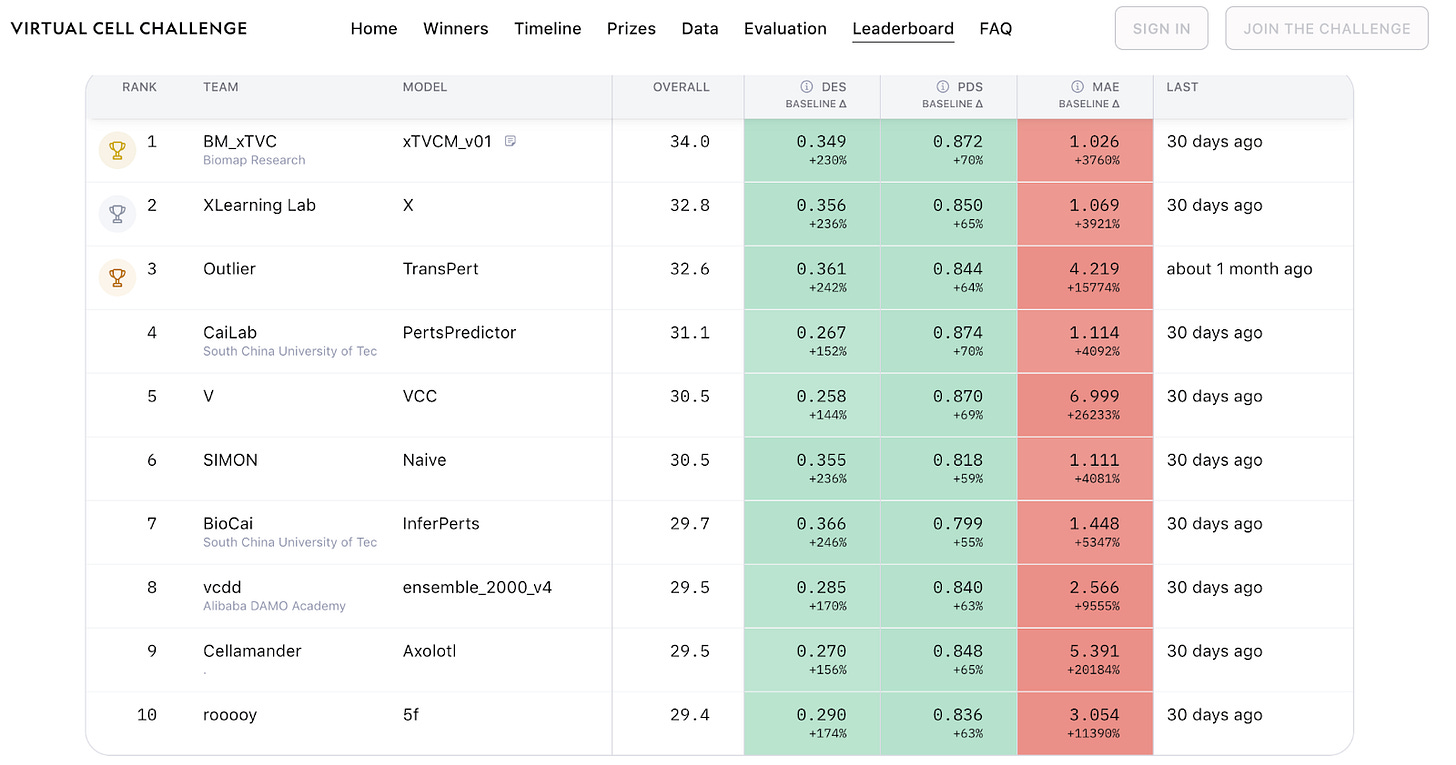

That fear was not hypothetical. Turbine AI later showed that a simple regression model trained on pseudobulk data, rather than individual cells, landed around 15th on the leaderboard. Their argument was blunt. Once you strip away redundancy and noise, the effective dataset size was closer to a few hundred samples than millions of cells.

When I asked Gio about this, he didn’t hesitate. It matched his experience exactly. Single-cell noise made many sophisticated approaches brittle, and pseudobulk representations often carried most of the usable signal.

Participants felt this viscerally. Large models failed to converge. Loss curves stayed flat for hours.

Compute bills climbed while biological insight stayed thin. When data is scarce in the ways that matter, complexity stops being impressive and starts being fragile.

Still, the nightmare scenario did not fully play out.

What actually won, and why that matters

Despite the fears, the top-performing teams did not simply deploy linear models and walk away. According to Gio, the winning approaches looked genuinely thoughtful. Hybrid models that mixed deep learning with statistical care and biological reasoning.

Pseudobulk representations showed up again and again. So did restraint. Many teams largely ignored mean absolute error across all genes and focused instead on perturbation discrimination and differential expression. That choice was not about gaming the system. It was about focusing on what felt biologically meaningful.

The surprise announcement of a Generalist Prize mid-competition raised eyebrows. In hindsight, Gio said it made sense. It rewarded models that behaved reasonably across multiple metrics, not just those that optimised one score aggressively. For many participants, that made the final outcomes feel more trustworthy.

Not perfect. Just credible.

Metrics were the real battleground

If you want to understand the Virtual Cell Challenge, start with metrics, not architectures.

Mean absolute error across roughly 20,000 genes sounds reasonable until you remember that most genes should not change under a given perturbation. Penalising models for noise in irrelevant genes is like grading a pianist on how well they play the silence between notes.

The Perturbation Discrimination Score sparked debate as well. Gio described long Discord threads dissecting its sensitivity to control choice and prediction magnitude. Teams learned quickly that scaling outputs could affect scores without necessarily improving biological correctness.

The deeper issue is uncomfortable but unavoidable. There is no single correct way to score predictions in this setting. RNA expression is a proxy for internal cell state, which itself is only loosely tied to phenotype. As Gio put it, we are scoring shadows of shadows and expecting clean answers.

Are we modelling cells, or just their fingerprints?

When I asked Gio whether we truly have virtual cells yet, his answer was blunt. Not really.

What we have are increasingly good models of transcriptional fingerprints. Predicting gene expression patterns under perturbation is useful, but it is not the same as modelling the full internal state of a cell. Doing this reliably for a single cell line, let alone across contexts, remains very hard.

That does not make the work pointless. RNA-seq remains one of the most reusable data types in biology. It connects assays. It travels well between labs. It gives us something shared to reason about. But it is still a proxy, and pretending otherwise only muddies the conversation.

What the community learned between the lines

Behind the leaderboard screenshots and blog posts, a smaller community formed around the challenge. Mostly on Discord. Dozens of participants, with a smaller core group actively debating metrics, data assumptions, and what should change next time.

There was talk of writing a collective letter critiquing the evaluation setup. It never materialized, not because of disagreement, but because people ran out of time. Jobs, grants, startups, life. Instead, the conversation shifted toward constructive reflection. How could the next challenge be better?

According to Gio, code sharing was limited, but write-ups and conceptual discussions were common. That may frustrate outsiders, but it reflects reality. This was not a Kaggle exercise. Many teams were balancing open science with real constraints.

If there is a next round

Most participants, Gio included, agree on a few improvements.

Metrics should focus on genes that actually matter for a given perturbation. Training and validation sets need far more perturbations, because 150 is tiny. And the community needs a better hub for discussion than a fragmented Discord channel.

There is already talk of follow-up challenges, including a Kaggle-style experiment focused specifically on evaluation. That is encouraging. Metrics deserve as much creativity and rigor as models.

A final word for builders

When I asked Gio what advice he would give to teams entering a future challenge, his answer was simple. Start simple.

Many teams burned weeks trying to force complex architectures to work, only to hit data limits they could not brute-force past. Start with something boring that runs. Then build up gradually.

Do not confuse frustration with progress. They feel similar in the moment.

The Virtual Cell Challenge did not give us virtual cells. But it did give the field something arguably more useful. A clearer picture of where the real difficulty lies. Sometimes, that clarity is exactly what moves a field forward.

Thanks for reading Kiin Bio Weekly! Big thanks to Gio for collaborating with us on this too! Check out his newsletter too for some posts that go deeper into different technical parts of the challenge!

💬 Get involved

We’re always looking to grow our community. If you’d like to get involved, contribute ideas or share something you’re building, fill out this form or reach out to me directly.

Connect With Us

Have any questions or suggestions for a post? We'd love to hear from you!

📧 Email Us | 📲 Follow on LinkedIn | 🌐 Visit Our Website

Really solid analysis of why the Challenge ended up being more about data limits than model architectures. The pseudobulk insight is spot-on, when you strip noise from single-cell data alot of the usable information collapses into way fewer effective samples. I've run into similiar issues in other bio contexts where raw data size looks massive but actual degrees of freedom are surprisingly small once you account for technical and biological redundancy.