🧬 Designing the Building Blocks of Life: A Primer on Structural Biology

What’s your biggest time sink in early drug discovery process?

From binders and enzymes to text-to-function models, the next wave of structural biology is about programming new molecules, not just predicting them.

We spoke to Siddhant Sharma, a computational biologist working at the Institute of Science and Technology, Austria, about how the field is evolving, and why the shift towards programmable biology is happening faster than anyone expected.

🔬 Why Protein Design Matters

For most of the past half-century, structural biology has been about discovery. We asked what structures nature builds, and how those structures explain biological function.

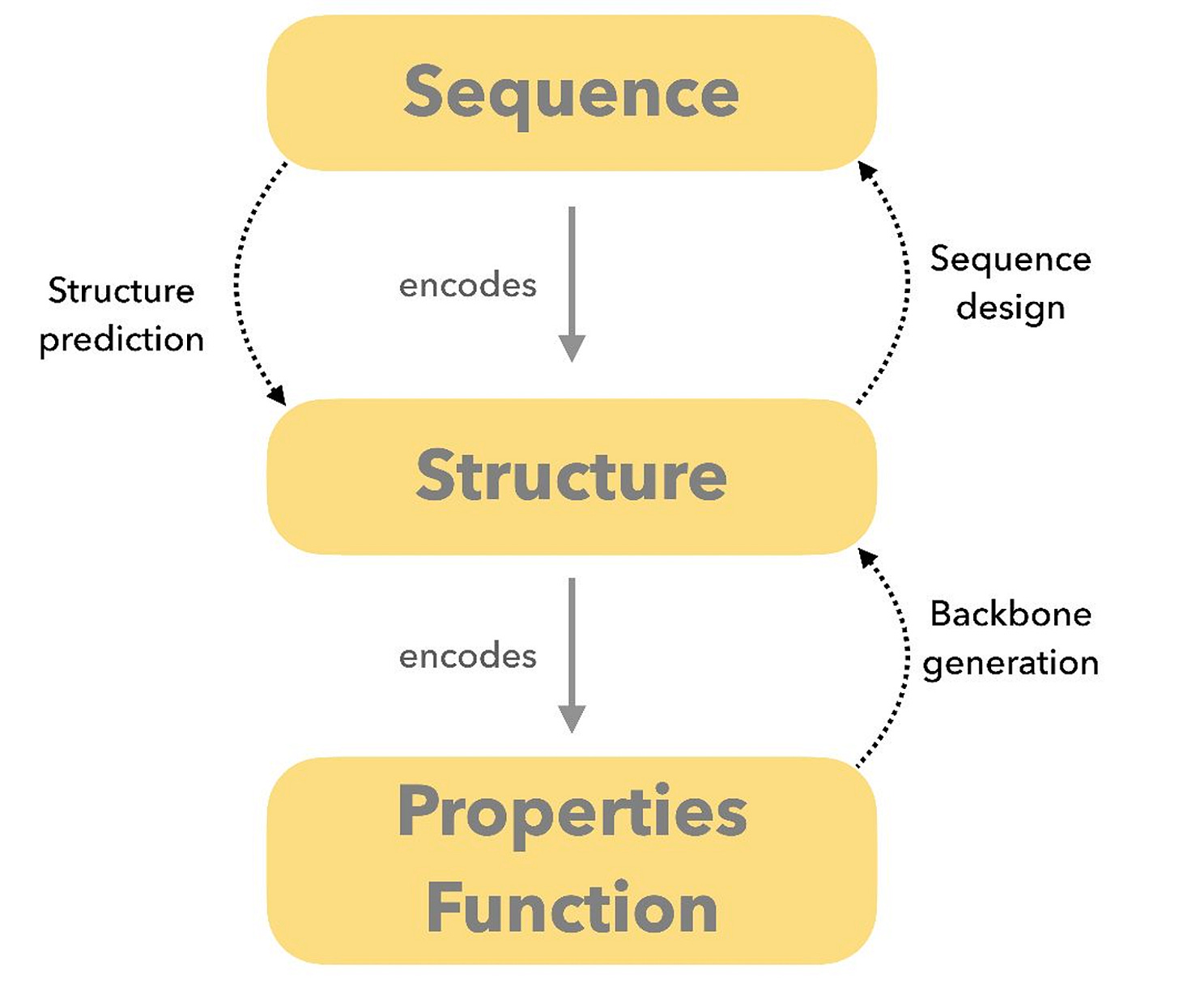

Protein design turns that question around. Instead of predicting what exists, it asks what could exist, and how to build it.

The goal is simple but transformative: to create proteins with precisely defined roles in binding, catalysis, or regulation.

Already, this shift is reshaping how medicines, materials, and diagnostics are made. De novo binder design is producing molecules that are smaller and more stable than antibodies. Engineered enzymes are being tuned for industrial catalysis and synthetic pathways. Multi-state switchable proteins are even acting like molecular logic gates, responding to light, phosphorylation, or ligand binding.

Protein design has become the bridge between understanding life and rewriting it.

⚗️ The Core Challenges

At the️ the centre of the field is the inverse folding problem: designing a sequence that folds into a desired three-dimensional structure or performs a particular function. While inverse folding dominates much of the current discussion, it is only one part of protein design. In practice, the field also includes forward folding, motif grafting, assembly design, and multi-state systems that do not fit neatly into a single formulation.

Even with today’s most powerful AI models, this remains far from solved. Structural datasets are still heavily biased towards proteins that crystallise easily, leaving major gaps for RNA, DNA, and disordered regions. Most models also ignore water molecules and charge states, which are vital for accurately capturing flexible or charged targets.

Models often inherit their own preferences. Tools such as Boltz or AlphaFold3 tend to favour backbones generated by their own systems, creating subtle circular biases. Few capture allosteric or transient binding sites, and computational predictions still run far ahead of experimental validation.

For now, the most trusted designs are those that have worked in the laboratory and those that can be reproduced using open tools.

🧫 A Short History of Protein Design

The story begins with the early days of crystallography and NMR, when frameworks such as Rosetta made it possible to design proteins on a computer for the first time.

The 2020s brought a step change. AlphaFold demonstrated that protein folding could be predicted with near-atomic precision. Soon after, models such as RoseTTAFold, Boltz-1, and RFdiffusion built on that success, moving from predicting to creating.

Today, the field is in what many researchers call its Cambrian explosion phase. New models appear almost every month. Some have been validated in wet labs, others remain exploratory, but all reflect a shift from understanding nature to engineering it.

🧩 How Protein Design Works

At a high level, protein design is often described through two complementary approaches. Forward folding predicts structure from sequence, while inverse folding designs sequences for a desired structure. In practice, most real-world pipelines blend both, depending on the constraints of the problem and the intended use case.

Typical workflows involve generating candidate backbones, assigning sequences, checking whether designs are likely to fold as intended, and ranking them using independent scoring metrics.

In practice, interface-focused metrics such as ipSAE are often used to assess binding confidence independently of the model that generated the structure.

These steps are rarely linear and are often iterated across multiple models to reduce bias and overfitting. Rather than serving as an end in themselves, these workflows act as enabling infrastructure for the downstream use cases that matter most.

A few practical principles guide design:

Favour hydrophobic hotspots at binding interfaces.

Avoid exposed hydrophilic regions.

Use structured scaffolds whenever possible.

Always start with a high-quality target structure, as poor inputs can mislead the entire process.

🧠 Key Use Cases and Gold Standards

🧬 Binder and Antibody Design

Binder design remains the most active area. Tools such as BindCraft and Boltz-Design are widely used to engineer high-affinity binders for therapeutics and diagnostics. Others, like BoltzGen, extend this to antibody-like scaffolds. Alongside these, newer antibody-focused platforms such as Chai Antibody, LatentX Antibody, Nabla Bio, and Germinal are pushing advances in antibody and minibinder design, particularly around specificity, developability, and manufacturability. De novo binders for intrinsically disordered regions and amyloids are an emerging focus, though they remain difficult to model because of their structural flexibility.

⚙️ Enzyme Design

Enzyme design has seen renewed interest through tools such as RosettaFold3,, RFD2, RFDiffusion 3 and riffdiff. Researchers are now designing enzymes that can catalyse reactions and also switch between conformations. The next generation of enzymes may act as dynamic systems that respond to light, ligands, or phosphorylation rather than as static catalysts.

🧱 General Protein Design

Models such as RFdiffusion and Evobind focus on designing new folds or improving stability. Antibody design, by contrast, remains a major challenge because of its immense sequence diversity.

Every lab uses a slightly different combination of tools. There is no single best model, only the right toolkit for a given question.

💡 Data, Trust, and the Open vs Commercial Divide

Open source continues to drive most of the progress in protein design. Communities such as RosettaCommons, Boltz seminars, and Colab Discord channels are where new models are released, benchmarked, and discussed.

Commercial platforms such as LatentLabs, Geoflow, and O Design have made these tools more accessible by prioritising usability, integration, and workflow cohesion. In most cases, the underlying methods overlap closely with open-source approaches, but the emphasis differs: academic tools tend to prioritise transparency and benchmarking, while commercial platforms focus on ease of use and interconnection across the pipeline.

Groups like Boltz are helping to bridge this gap by maintaining open-source releases while collaborating with industry partners. Across the field, trust and reproducibility remain the key measures of success.

🚀 Future Directions

🌐 Unified Design Across Proteins, DNA, and RNA

Structural biology has traditionally treated proteins, DNA, and RNA as separate problems, even though they function together in nature. The next step is to design across all three.

Data scarcity remains a challenge, with few high-resolution structures of protein–DNA or protein-RNA complexes. Yet new tools such as NA-MPNN and RFDpoly are beginning to bridge the gap, introducing early examples of multimodal co-design.

The long-term goal is a unified framework that can model complete molecular assemblies rather than isolated proteins, capturing how biological systems actually work.

🧬 Ensemble design pipelines

Increasingly, no single model is expected to solve protein design end to end. Practical systems now orchestrate multiple models for generation, scoring, refinement, and validation, combining their strengths while reducing individual biases. This ensemble-based approach is becoming a defining feature of modern protein design workflows.

💬 From Text to Function

A newer generation of approaches points towards text-to-function workflows, where scientists describe a desired outcome in plain language and design pipelines translate that intent into candidate structures. While early systems illustrate what this could look like, the broader shift is towards intent-driven, modular design rather than reliance on any single model.

Behind this movement is a shift towards modularity. Instead of relying on one master model, researchers are combining smaller systems for generation, scoring, and simulation. This modular design reduces artefacts, speeds up iteration, and makes it easier to benchmark new models.

Hardware acceleration is also transforming the field. NVIDIA-optimised pipelines have cut GPU runtimes significantly, while AlphaFold3’s ligand-aware predictions are merging structural and functional modelling into a single step.

Together, these developments are moving the field towards programmable biology, where researchers can move smoothly from text to structure to experiment.

🔭 Conclusion

Protein design is rapidly evolving from analysis to engineering. Where structural biology once mapped nature’s blueprints, it is now beginning to draw its own.

Progress depends on open data, modular pipelines, and validation that connects computational prediction with laboratory results. As models mature and become more interpretable, the idea of describing a function in text and watching a new molecule take shape is no longer science fiction. It is the future of structural biology.

Thanks for reading Kiin Bio Weekly!

💬 Get involved

We’re always looking to grow our community. If you’d like to get involved, contribute ideas or share something you’re building, fill out this form or reach out to me directly.

Subscribe now to stay at the forefront of AI in Life Science and keep up with this upcoming season of deep dives.

Connect With Us

Have questions on this or suggestions for our next deep dive? We’d love to hear from you!

📧 Email Us | 📲 Follow on LinkedIn | 🌐 Visit Our Website