🧬 MOLECULE: Why Protein Motion Changes How We Classify Drug Action

Deep Dive | Edition 12

Welcome back to the deep dive, where we break down the AI tools and data reshaping how new drugs are discovered. In each edition, we speak directly with the teams behind these tools to explain what they solve, how they work and where they are going next.

What’s your biggest time sink in early drug discovery process?

Proteins don’t sit still. So why do our models pretend they do?

If you work anywhere near structure-based drug discovery, you’ve heard the line a hundred times: proteins are dynamic systems. They shift, breathe, rearrange. Function emerges from motion, not just form.

And yet, most machine learning models still treat proteins like statues.

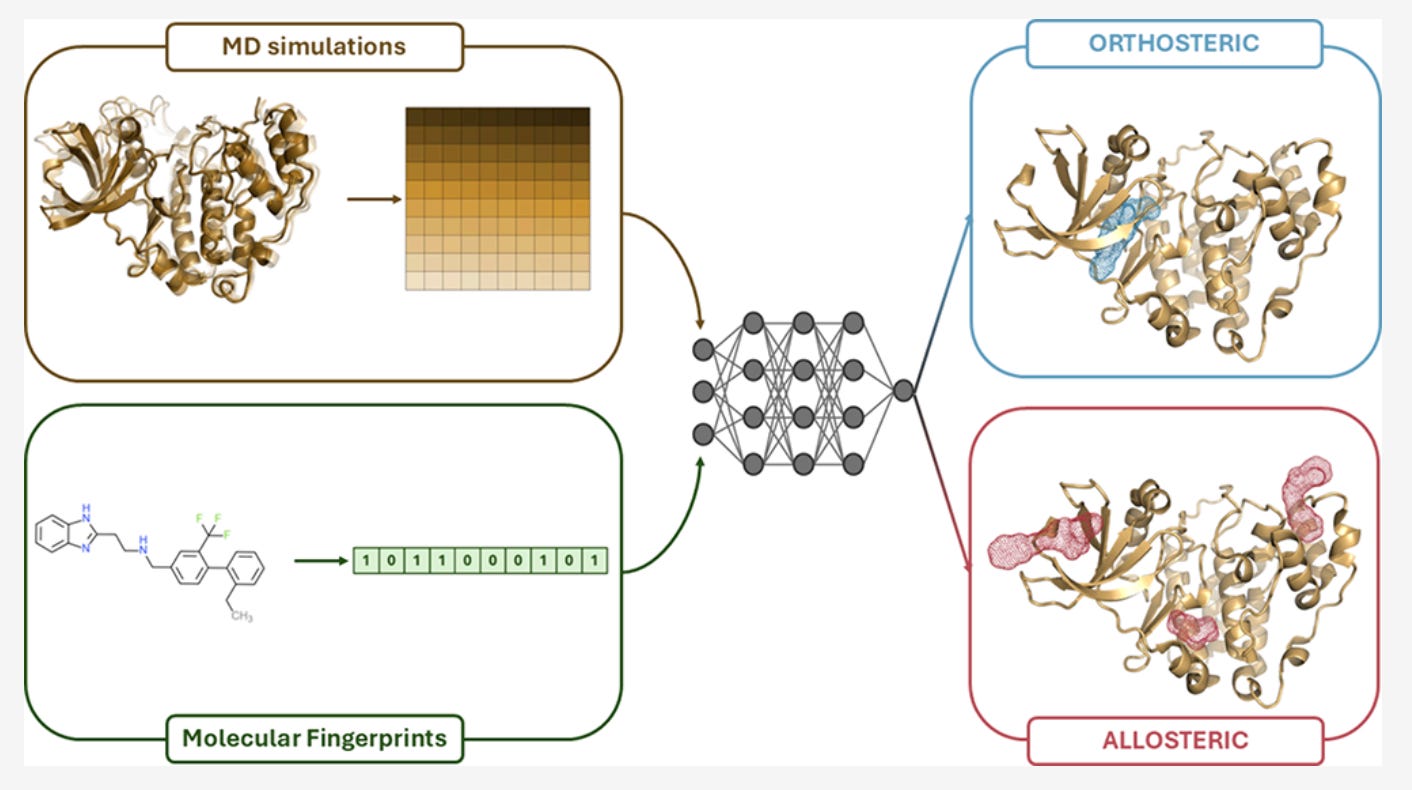

That disconnect is exactly what pushed the MOLECULE team at the University of Pavia to rethink how ligand activity is predicted. Their recent paper introduces a deep learning model that combines molecular dynamics with chemical structure to classify ligands as orthosteric or allosteric and, crucially, to admit when it isn’t sure

When we spoke with the authors, the motivation came up immediately. “Allostery is a dynamic phenomenon,” Giorgio Colombo told us. “What happens in one site has to travel through the protein. You only catch that if you include dynamics”

Simple idea. Big implications.

🔴The problem: static confidence in a moving system

Most ML models in drug discovery lean heavily on fingerprints. They’re cheap, standardised, and available for millions of compounds. That convenience has shaped the field.

But Elena Frasnetti was blunt about the limitations. “Especially when you look at allosteric activity, it’s a bit naive to use only the chemical structure of the ligand,” she said. “We saw that fingerprints alone couldn’t really grasp this behaviour”

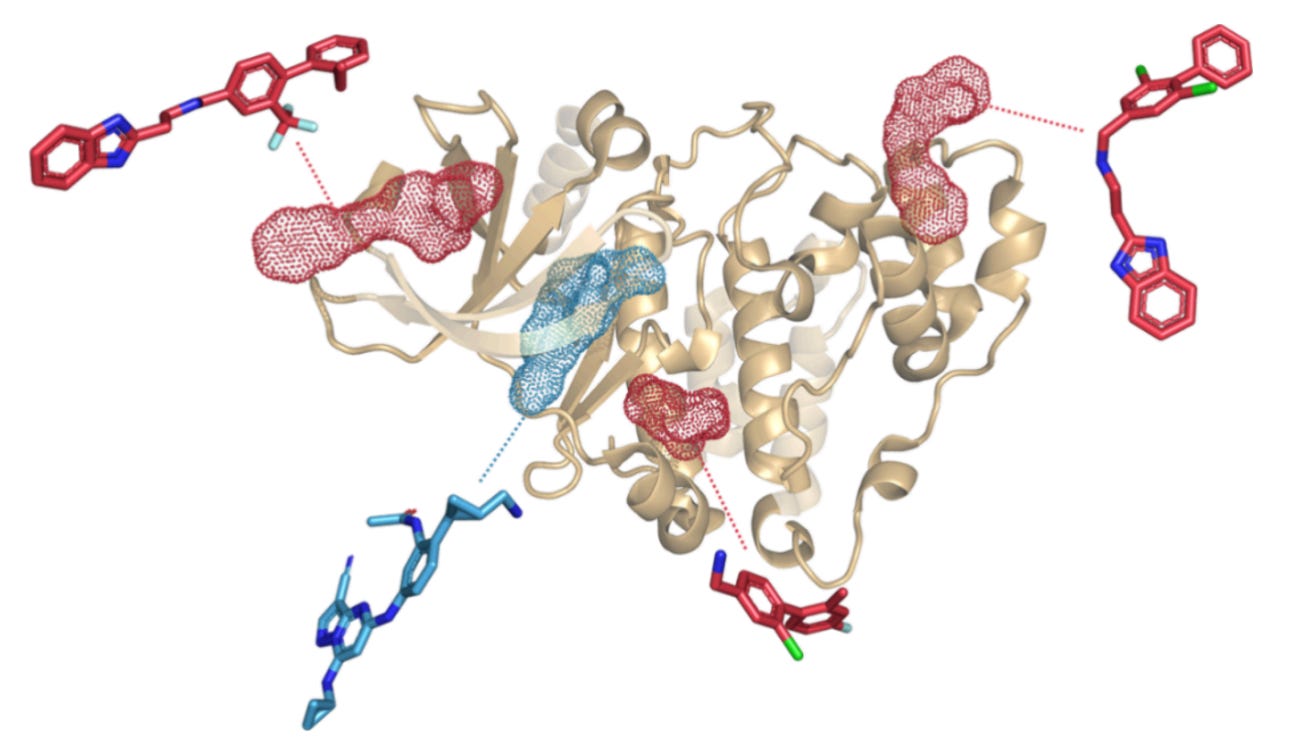

Kinases make this painfully obvious. Their ATP binding sites are highly conserved, which means orthosteric inhibitors often struggle with selectivity. Allosteric ligands, on the other hand, act through less conserved regions and often tune activity rather than shutting it down.

That tuning shows up in protein motion. Miss the motion, and you miss the mechanism.

The downstream cost is real. Misclassify a ligand’s mode of action, and you chase the wrong selectivity profile. Worse, you do it with high confidence. False positives are expensive. False certainty is worse.

💡The approach: let chemistry and motion speak separately

The central design choice in MOLECULE is not flashy, but it’s deliberate: don’t force different data types into the same box.

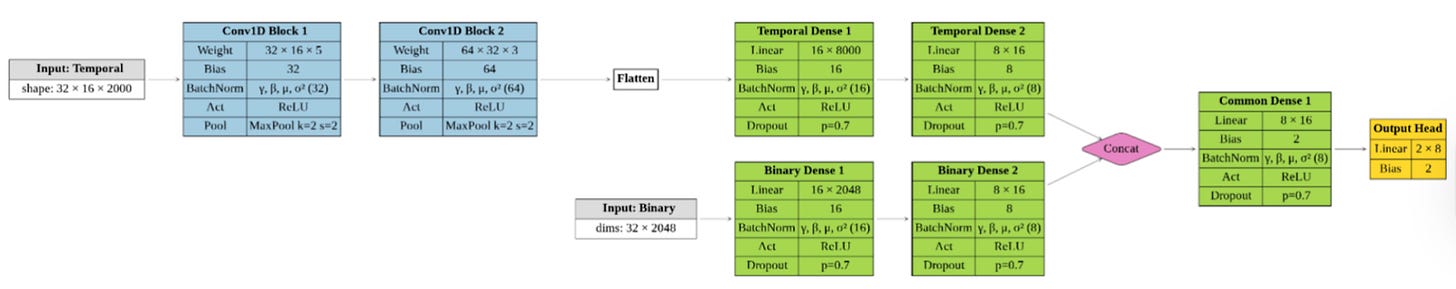

Instead, the model uses a dual-branch architecture. One branch processes molecular dynamics time series: RMSDs and residue-residue distances across full trajectories. The other handles static ligand fingerprints. Each branch learns independently before their representations are combined for classification.

“The fingerprints and the molecular dynamics data are very different,” Ivan Cucchi explained. “We wanted to extract all the information from both”

For the temporal data, the team chose convolutional networks rather than more complex sequence models. Not because transformers are out of fashion, but because CNNs are efficient, stable, and fast. Training takes minutes. Predictions take seconds. That matters if you want this to run in real workflows, not just benchmarks.

The model also uses entropy-regularised focal loss, a way of encouraging learning on difficult cases while discouraging overconfident guesses. It’s a technical choice with a very human goal: fewer confident mistakes.

🔬Why this feels different: uncertainty is part of the output

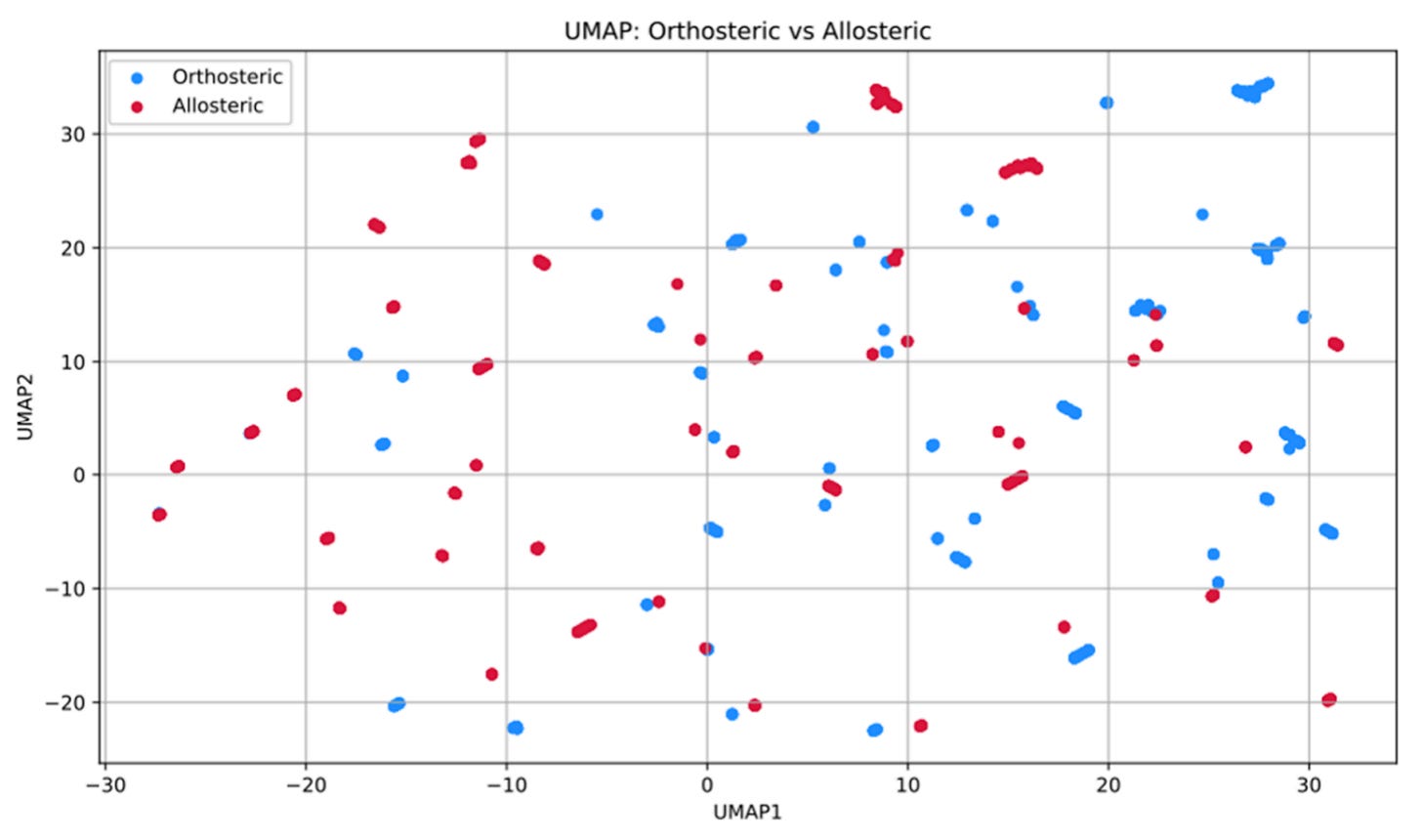

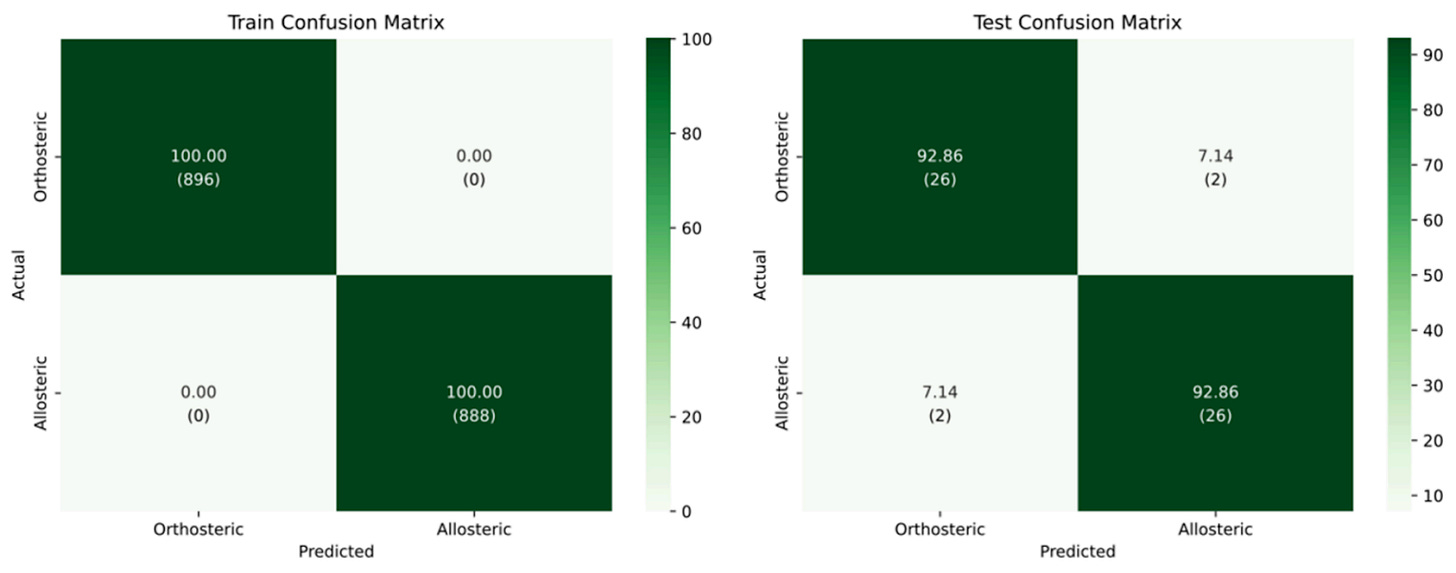

One of the most interesting parts of the work isn’t accuracy, though the numbers are strong. It’s the decision to let the model abstain.

Rather than forcing every prediction into “orthosteric” or “allosteric,” MOLECULE uses confidence thresholds. Predictions below a chosen threshold are assigned to an explicit “uncertain” category.

As Cucchi put it, “This is a reliable instrument for real-life projects, not just academic ones”

That mindset shows up throughout the paper. At moderate thresholds, the model maintains high performance while filtering ambiguous cases. Raise the threshold, and coverage drops, but reliability increases. It’s a trade-off you can choose, rather than one hidden inside a softmax score.

This matters because drug discovery rarely operates at internet scale. “In real-world settings, you don’t have millions of molecules,” Colombo emphasised. “You work with limited data, and the model has to reflect that”

🧠Dynamics matter, even when you don’t have them

Feature attribution analysis makes one thing clear: when molecular dynamics are available, they dominate the predictive signal. Motion carries information fingerprints simply can’t.

But the team didn’t stop there. They built an imputation branch that reconstructs a latent dynamics representation from fingerprints alone. Performance drops, as expected, but the model’s uncertainty behaviour remains sensible. It becomes more cautious, not more confident.

That’s an important distinction. There’s no claim that chemistry alone replaces physics. Instead, there’s a graded understanding of trust depending on what information you provide.

It’s a pragmatic solution to a very real constraint.

🔮The future: more data, fewer illusions

The authors are careful about generalisation. Right now, MOLECULE is trained on kinases. Whether it transfers cleanly to other protein families remains open.

Frasnetti pointed to the real bottleneck: access to shared molecular dynamics data. Generating trajectories is expensive, slow, and unevenly distributed across labs

Without broader data sharing, progress stays fragmented.

There are encouraging signs. Efforts to build MD trajectory repositories, closer to what the PDB did for structures, could change the landscape. If that happens, approaches like MOLECULE become far more portable.

Zooming out, the work hints at a quieter shift in model evaluation. Not just “how often is it right?” but “does it know when it might be wrong?”

In systems that never stop moving, that kind of honesty might be the most useful feature of all.

📄 Read the paper!

⚙️ Access the model on Github.

👨🔬 Get in touch with Giorgio, Elena or Ivan.

Thanks for reading Kiin Bio Weekly!

💬 Get involved

We’re always looking to grow our community. If you’d like to get involved, contribute ideas or share something you’re building, fill out this form or reach out to me directly.

Subscribe now to stay at the forefront of AI in Life Science and keep up with this upcoming season of deep dives.

Connect With Us

Have questions on this or suggestions for our next deep dive? We’d love to hear from you!

📧 Email Us | 📲 Follow on LinkedIn | 🌐 Visit Our Website