RFdiffusion3: Protein design at all-atom resolution

Deep Dive | Edition 4

Welcome back to the deep dive, where we break down the AI tools and data reshaping how new drugs are discovered. In each edition, we speak directly with the teams behind these tools to explain what they solve, how they work and where they are going next.

Today we’re diving into RFdiffusion 3 (RFD3), the newest model from the Institute for Protein Design (IPD) at the University of Washington. We spoke with Jasper Butcher, the lead developer, whose work bridges structural biology and generative machine learning. Jasper joined the Baker Lab as an intern during the first RFdiffusion project and has since helped guide its evolution from residue-level to all-atom design.

🔴 The Problem

It’s well established now that deep learning has completely reset how we predict protein structures. Tools such as AlphaFold and RoseTTAFold can tell us, with pretty remarkable accuracy, what nature has already built but they still struggle to create something new.

Designing functional proteins is a very different challenge. Earlier generations of RFdiffusion operated at the (coarser) residue level, generating backbone coordinates and filling in side-chains later. That simplification kept computation tractable but ignored much of the underlying chemistry like the precise hydrogen bonds, electrostatics, and catalytic alignments that determine whether a protein actually works. Previous models have therefore often required the model to ‘imagine’ the sidechain placements during generation and therefore only implicitly modelled the full generated protein.

As Jasper explained, the team wanted to move beyond shape generation to model chemistry itself:

“We wanted to transform AlphaFold3’s components into a generative architecture made for design, not folding.”

RFdiffusion 2 introduced active-site scaffolding but it didn’t reason about side-chains or flexible ligands in a simple manner. The next leap required representing every atom directly natively to the architecture.

💡 The Idea

According to Jasper, the RFD3 project began around January 25, developed alongside the IPD’s internal reproduction of AlphaFold3 - RosettaFold3.

AF3 was a watershed moment for protein design and we realised we should do design models entirely differently,” Jasper said.

He added that the team realised they could repurpose AF3’s predictive framework into a generative system for design, as has been done for RosettaFold -> RFdiffusion1, RF2aa -> RFdiffusion2 and now AF3 (RF3) -> RFdiffusion3.

That reproduction inspired the team to invert the AF3 diffusion framework: instead of predicting structure from sequence, they would generate sequence by generating atomic structure from noise.

They removed AF3’s large sequence-processing trunk (which is argued unnecessary when the goal is design) and replaced it with a transformer-based U-Net that models atomic coordinates directly. Each amino acid is represented by four backbone atoms and up to ten side-chain atoms, resulting in a uniform 14-atom representation across residues.

Despite this finer resolution, RFD3 is surprisingly efficient: about 168 million parameters, half the size of AF3 and roughly ten times faster than RFdiffusion 2, the previous state-of-the-art generative model for the design of enzymes. Sparse attention and cross-attention pooling are new features that let the network capture local atomic geometry while maintaining global coherence between side-chains and backbone.

“RFD3 represents roughly an order-of-magnitude improvement over RFD2 in both pass rate and speed; the combined effect of both is what makes RFD3 so impactful. The increased speed means we can simply run more designs for less compute, which turned out to be one of the biggest reasons people got excited about using it for design even very early on in development.”

The all-atom representation unlocks a new set of atom-level conditioning mechanisms: tunable dials that let researchers steer generation for their problem of interest:

“Hydrogen bonding, solvent accessibility, and the protein’s centre of mass are powerful conditioning tools which allow fine-grained control of the designs coming out of the model,” he said, “giving designers much finer and flexible control than before.”

Each mechanism can be combined freely, enabling precise control over how a design folds, binds, or assembles.

“There’s a huge number of tasks we can now tackle with one unified model; DNA binders, protein binders, symmetric oligomers, ligand binders, enzymes; Integrating all these constraints into a single model was a major challenge with the project.” Jasper added. “Moving to an all-atom formulation gave us a general solution; it lets us reason about everything from ligands to nucleic acids without retraining for each case.”

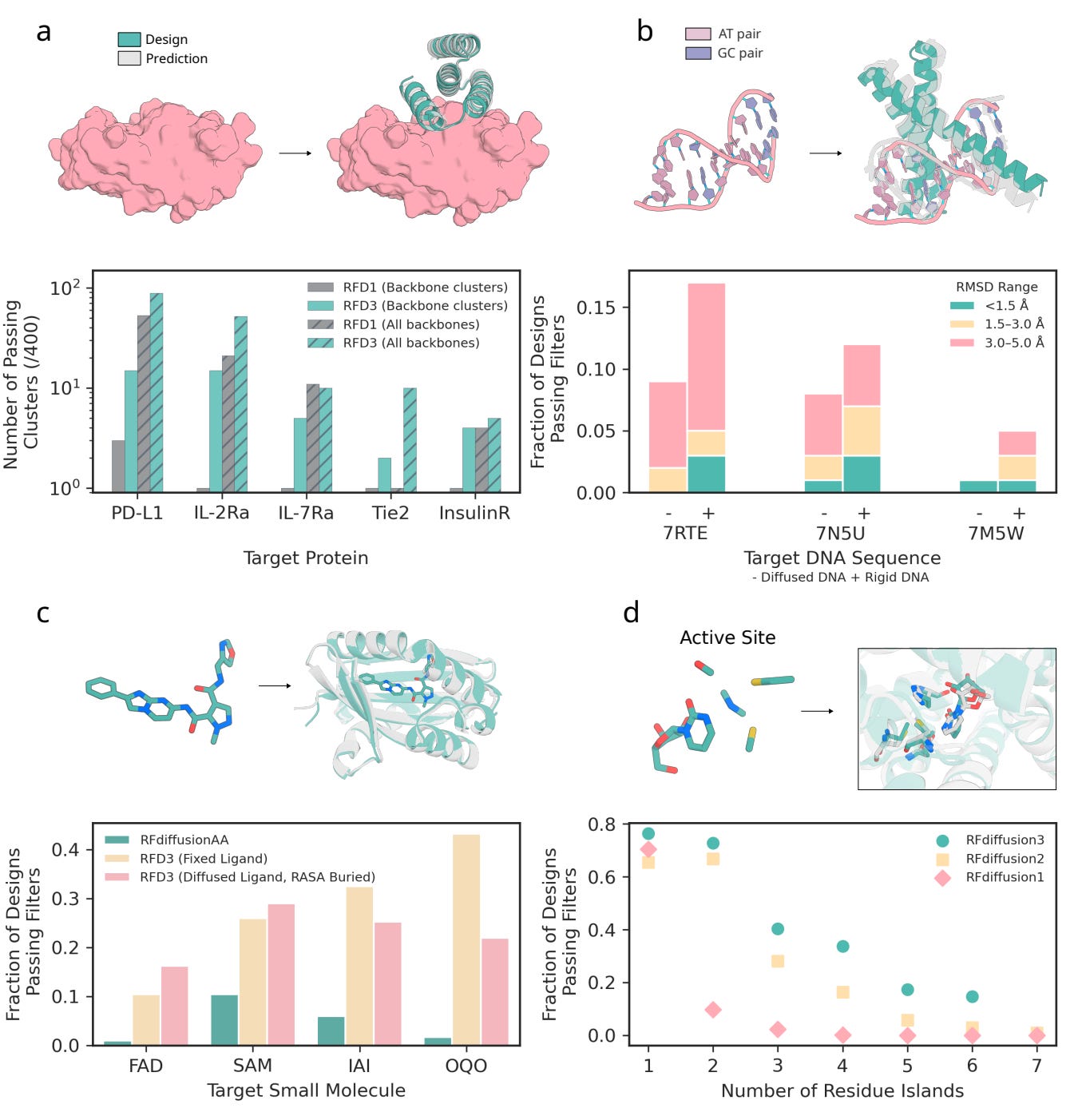

All-atom protein design with RFdiffusion3

📊 What About the Training Data?

RFD3 was trained on all complexes in the Protein Data Bank (PDB), spanning protein-protein, protein-small-molecule and protein-DNA interactions along with high-quality structures distilled from AlphaFold 2 predictions. Each entry was annotated with geometric and functional features such as hydrogen-bond donors and acceptors, ligand contacts, and catalytic motifs.

Training diffusion models occurs by “noising” native structures to different levels and teaching the network to recover both backbone and side-chain atom positions. This allows the model to learn how realistic proteins emerge from chaos, atom by atom.

To avoid overfitting, the team used a hierarchical training schedule: pre-training on a broad mix of PDB and AlphaFold data, then fine-tuning on interaction-rich examples such as DNA and protein-protein complexes. The final model distils the structural diversity of nearly everything known about biomolecular interactions into a single generative framework.

Global- and atom-level conditioning with RFdiffusion3

🔬 Why It’s Different

RFD3 represents a clear philosophical shift: from specialised residue-level networks toward a general-purpose all-atom generator capable of tackling a wider range of design scenarios than ever before.

In benchmarks, RFD3 delivers standout gains to:

Protein-protein binders: Outperforming RFdiffusion 1 on four of five therapeutic targets, producing more diverse binding geometries.

DNA-binding proteins: Achieves ≈ 9 % success on unseen DNA sequences (< 5 Å RMSD): a meaningful advance in a low-yield category, notoriously requiring complex and compute-intensive pipelines with existing methods.

Small-molecule binders: Jointly generating both ligand and protein conformations, eliminating the need for rigid-ligand inputs.

Enzyme scaffolds: Outperforms RFdiffusion 2 on 37 of 41 active-site benchmarks, particularly in cases with multiple disconnected catalytic residues.

These computational results translated to the lab: one designed DNA-binding protein bound its target with an EC₅₀ of ≈ 6 µM, and a series of cysteine hydrolases, the most active of which achieved a catalytic efficiency of Kcat/Km ≈ 3557 that surpassed earlier de novo designs.

For those who don’t speak this language, an EC₅₀ in the low micromolar range indicates a relatively strong and specific binding interaction, while a high Kcat/Km reflects how efficiently an enzyme converts its substrate to product; in this case, showing that the designed enzyme performs comparably to natural catalytic proteins.

By generating side-chains and backbones together, RFD3 captures the physical logic of molecular recognition, not just the architecture of a fold but the chemistry that makes it functional.

🔮 The Future

Jasper described RFD3 as the foundation for what comes next:

“RFD3 lays new foundations for design; the focus is on improving prediction numbers and making each task perform better, lower computational costs and improve accessibility.”

A central challenge ahead is bridging the gap between in silico predictions and in vitro success:

“One of the big next steps is improving how folding predictions correlate with experimental success. Current oracles don’t always capture the subtle differences that decide if an enzyme actually works.”

Ultimately, he sees RFD3 as a stepping stone toward generalist protein-design models capable of continuous iteration between design, sequence optimisation, and experiment.

“The field is moving really fast toward generalist models and, ultimately, consistently designing high-quality drugs, catalysts and beyond.”

📄 Read the paper!

⚙️ The code is coming out soon.

👨🔬 Get in touch with Jasper.

Thanks for reading!

Did you find this newsletter insightful? Share it with a colleague!

Subscribe Now to stay at the forefront of AI in Life Science and keep up with this upcoming season of deep dives.

Connect With Us

Have questions or suggestions for our next deep dive? We’d love to hear from you!

📧 Email Us | 📲 Follow on LinkedIn | 🌐 Visit Our Website

Thanks for the article! Very interesting.

They developed it quite quickly - just a few months, if they started on January. Impressive!

U-Nets are cool in terms of architecture, with layers zooming in and out of the picture.